Robots in the classroom

Marshall students design, build for competition

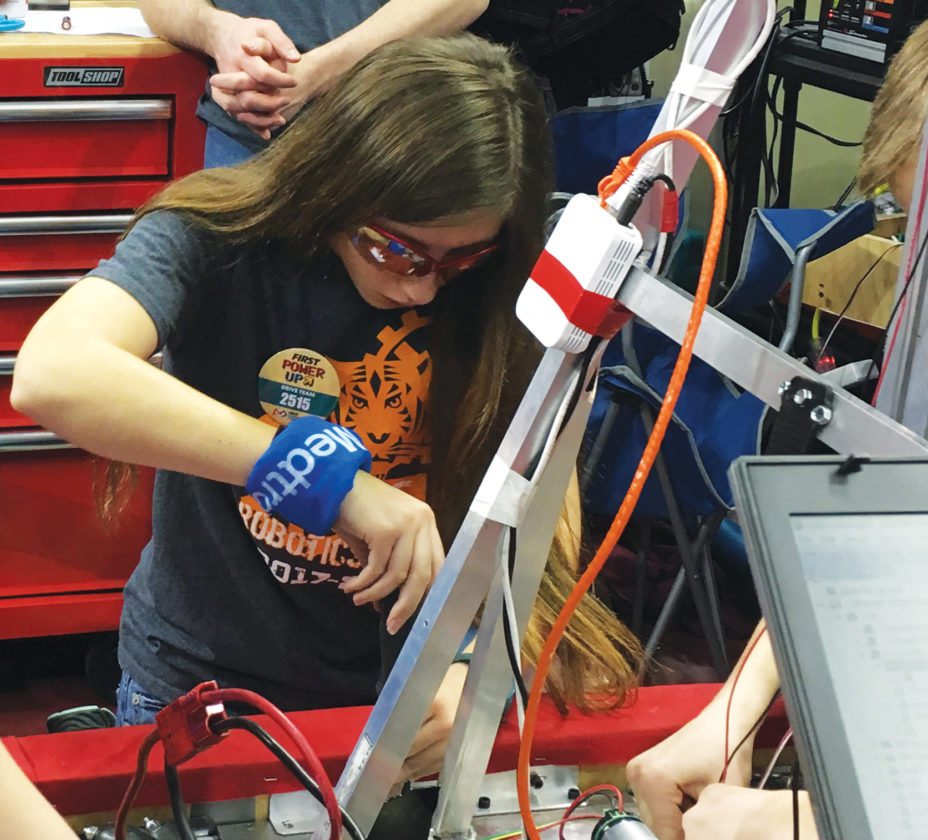

Photo courtesy of Pam Fier-Hansen MHS senior Nichole Sample makes some repairs on the team’s robot during the 2018 FIRST Robotics Competition recently.

MARSHALL — At its last board meeting, Marshall School Board members had the opportunity to learn about the Marshall High School robotics program — a program that is growing in Minnesota and beyond.

“There are now more robotics programs in Minnesota than hockey teams,” MHS science teacher Pam Fier-Hansen said. “Robotics helps build skills for the 21st century.”

As part of a different challenge each year, robotics teams from Minnesota — similar to others across the nation and throughout the world — have 6 weeks to design, build and program a robot.

“Robotics is an excellent program for students to be involved in because it teaches them so many different skills,” Fier-Hansen said. “In addition to learning how to design, build and program the robot, the students learn how to collaborate and solve problems. As part of the FIRST Robotics Competition, they are also judged on how well they can explain the design to judges. They are also responsible to follow a budget for the robot.”

Along with Sharon Jensen, Fier-Hansen is instrumental in organizing the program and supervising the students.

“Typically, we have between 15 and 25 students involved in the program,” Fier-Hansen said. “(Sharon) and I organize meetings, recruit students and supervise them during the competition.”

John DeCramer is the lead mentor.

“John has been working with the robotics program in Marshall since it started about 10 years ago,” Fier-Hansen said. “He oversees the building of the robot. He teaches our students how to use equipment and supervises putting the robot together at BH Electronics.”

The three mentors were joined by a handful of MHS robotics members who also shared their experience in the program with board members.

Senior Jett Skrien explained that BH Electronics is where nearly all the robot building takes place.

“John typically heads that up,” Skrien said. “He’s kind of the safety guy and also because it’s pretty much his location. They provide all of the tools — the drills, the saws, the screws, the aluminum — and that’s where about 99 percent of our work takes place.”

Senior David Black talked about the evolving process of the build.

“These wheels were really our Holy Grail of build projects this year,” he said as he held up the object with wheels for board members to see. “These wheels went through probably 20 different iterations before we got something that worked acceptably to go on our robot and actually performed for us in the competition.”

Black said the team used mecanum wheels.

“They allow you to drive either forward or backward and then without turning the wheels — so the orientation of the wheels stays the same — but they turn at different speeds and different directions,” Black said. “It allows you to turn in place or just drive sideways or at any angle 360 degrees. So if your robot is going north, you can drive to any point on the compass without changing the direction your robot is pointing.”

J.P. Rabaey talked about the challenges of programming the robot, made more difficult this year because of a software change.

“We undertook a huge new programming project,” Rabaey said. “We switched from LabVIEW, which is a comfortable software that we’ve used for many, many years, to Java, which is the language that the academic community uses.

Rabaey said that while Java “dovetails really nicely now with some high school courses,” the switch gave them “a whole new set of experiences.”

“Every code loop is running over and over again,” he said. “So continuous operation throws off those of us who are used to a project that goes down, does its thing and then turns off. It posed a lot of challenges.”

Ivan Hudson reiterates what Rabaey said about the challenges.

“I did learn a lot from the programming this year,” Hudson said. “It’s a lot different having all the loops of code running. I’d never done anything like that before.”

Reed Schuerman spoke about the process of putting wooden macrame beads as their wheels early on.

“It slipped a whole lot, so we weren’t able to move around,” he said. “Then we tried shrink wrapping, hoping that it would add more friction so we wouldn’t slip as much. It worked a little bit, but it wasn’t the greatest. We ended up having BH cast it and they made us, I don’t know, a hundred or so of these wheels. I drilled them all out and we put in the stuff. They worked pretty good at the competition.”

Schuerman ended up being selected to be the driver for the robot. When board member Bill Swope asked him how he was chosen, Schuerman said basically it was because his dad (Kelly Schuerman) was the lead programmer and that he was working alongside him most of the time.

“When my dad was deciding what buttons would do what, I was there helping him decide,” Reed Schuerman said. “That made it easy. It was me or J.P., and he ended up not being able to go to the competition.”

Senior Nichole Sample told board members about the competition aspect.

“The first day is basically set up,” she said. “So we get into the pit — we set up and bring in all our tools and the robot — and pass inspection because you have to be within certain parameters and have everything functioning properly. Then you get to hope and pray it works the next day.”

Sample said she thinks the inspection process went more smoothly this year than in past years. Once getting the OK, it’s competition time, she said.

“You compete 4-5 times a day sometimes,” Sample said. “You compete nine times over three days. We’re randomly grouped into teams of three, so it’s 3 on 3 per match, so you do have to do a lot of cooperation and a lot of communication with those other teams. Then in between each of your matches — you might have an hour or 20 minutes — you’re just trying to fix everything, keep it working for the entire day, switching out batteries and keeping it charged and in one piece. And you go up or down based on your ranking and how you do with your teams.”

Sample explained that this year’s competitive task was to move blocks and take possession of different switches.

“Three different teams pair into one alliance that goes agains the other alliance,” she said. “You’d switch bumpers — you’d either have blue or red bumpers. There was a big switch in the middle and you wanted to move blocks and take possession of that, and based on how many seconds you had possession for, you could get points. You could also get points for crossing a line in the first few seconds of the match, when the robot is in autonomous mode.”

Schuerman said the team had to code the robot to operate in autonomous mode.

“As the match starts, a code is sent to a robot and it will perform the action,” he said. “We had it coded to drive straight forward. Ours curved a little bit at the end, but we still passed the line and got 5 points.”

A short video showed how the robot picked up blocks and performed other functions.

“See how I’m grabbing blocks and I’m bringing it over to them so they can push them in the vault,” Schuerman said. “For each one, we got 5 extra points. With three in, we could get elevate, which is 30 points.”

Board member Matt Coleman asked team members if they strategized with the students on the other two teams before starting each competition. Schuerman said they did, including the last 30 seconds.

“They set off an alarm with 30 seconds left and every team tries to climb — there’s a wrung about a foot wide — and three robots are supposed to climb to get the max amount points,” Schuerman said. “It’s really difficult. For us, we had a climbing mechanism, but it didn’t work too well. So I just tried to park on the platform to get 5 points. If we had to do over again, we’d make the elevator faster.”

Board chair Jeff Chapman said he thought the effort was “pretty impressive.”

“That’s what engineers do,” he said. “They evaluate everything and they make changes. What great learning experiences.”

While the mentors — including Kelly Schuerman, Curt Timmerman, Joe Hudson, Cory Perrault and Randy Schultz, along with Fier-Hansen, Jensen and DeCramer — are there for guidance, the students are responsible for figuring things out.

“That’s the whole idea,” DeCramer said. “They need to figure it out.”

The robotics team also took time to thank all of their sponsors — BH Electronics, Action TrackChair, Monsanto, Fagen Inc., Next Era Energy, FIRST Robotics, Bend Rite, Medtronic and MPS — and others who helped along the way.

“We’ve had really tremendous support from the community and we really appreciate it,” Fier-Hansen said.

Along with a $5,000 registration fee just to get into the FIRST Robotics Competition, there are a lot of material costs as well.

“If we added up our basic raw material — as we start out with raw aluminum and things like that — it would be about $2,500 to purchase,” DeCramer said. “That’s just the start. We were fortunate, with the help of Action Track, to be able to make a wheel. If we had to go out and purchase that wheel, which we could, it was about $125 to $150 a wheel. If we look at the raw material that did go into it, it was in the range of $30. And most of the materials were supplied by our sponsors. In reality, we got by a little less than that.”

The mentors said that robotics aligns nicely with many of the career and technical classes at MPS — classes like pre-engineering, metalworking and woodworking.

“It’s a good foundation and worth building on a little bit more,” DeCramer said.